INVESTIGATION No. 4 The multiple identities of the NAHAM-4

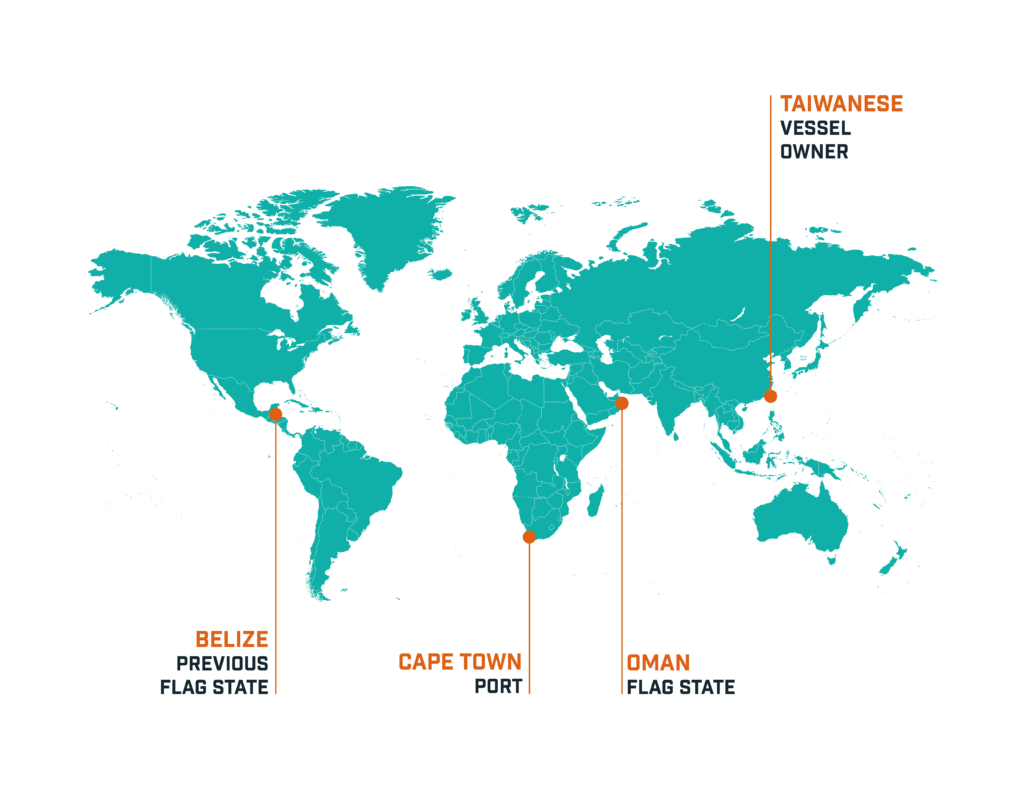

The NAHAM-4 investigation highlights the extent of vessel identity fraud occurring in the fishing industry. The vessel, a tuna longliner was detained and later confiscated by South African authorities due to uncertainty about its identity, meanwhile at least four other vessels were identified as having operated with the name NAHAM-4. A global system of vessel identification, including using mandatory IMO numbers on industrial fishing vessels, is essential to overcome these issues.

Key events

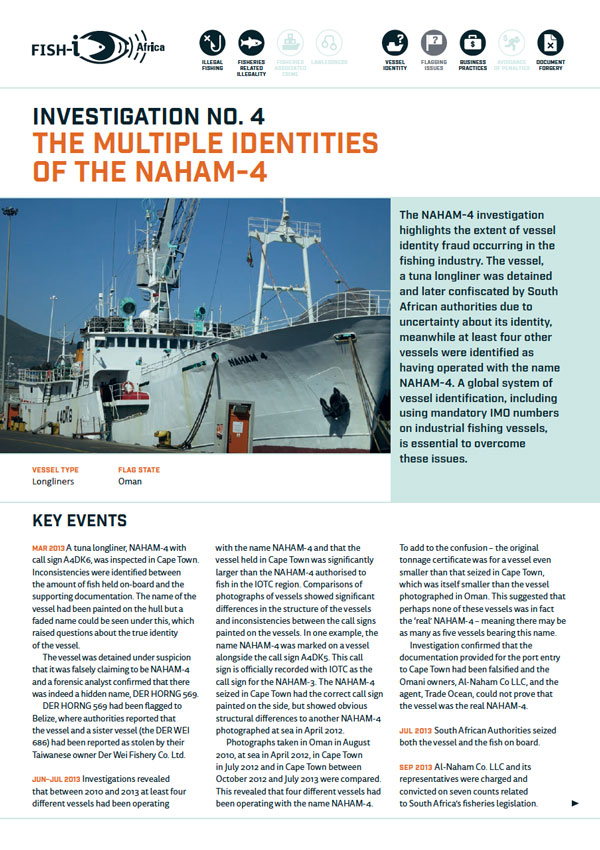

March 2013: A tuna long-liner, NAHAM-4 with call sign A4DK6, was inspected in Cape Town. Inconsistencies between the amount of fish held on-board and the supporting documentation were identified. The name of the vessel had been painted on the hull but a faded name could be seen under this, which raised questions about the identity of the vessel.

The vessel was detained under suspicion that it was falsely claiming to be NAHAM-4 and a South African Police Service Forensic Analyst confirmed that there was indeed a hidden name, that of DER HORNG 569. DER HORNG 569 was historically flagged to Belize whose authorities reported that the DER HORNG 569 and a sister vessel the DER WEI 686 had been reported as stolen by their Taiwanese owner Der Wei Fishery Co. Ltd.

June – July 2013: Investigations revealed that between 2010 and 2013 four different vessels had been operating with the name NAHAM-4 and that the vessel held in Cape Town was significantly larger than the NAHAM-4 that was authorised to fish in the IOTC region. Comparisons of photographs of vessels showed significant differences in the structure of the vessels and inconsistencies between the call signs painted on the vessels. In one example, the name NAHAM-4 was marked on a vessel alongside the call sign A4DK5, this call sign is officially recorded with IOTC as the call sign for the NAHAM-3. The NAHAM-4 seized in Cape Town had the correct call sign painted on the side, but showed obvious structural differences to another NAHAM-4 photographed at sea in April 2012.

Photographs were compared from Oman in August 2010, at sea in April 2012, on the synchrolift in Cape Town in July 2012 and in Cape Town between October 2012 and July 2013 these showed that four different vessels had been operating with the name NAHAM-4. The vessel photographed in Oman appeared to be larger than the vessel seized in Cape Town and the original tonnage certificate was for a vessel even smaller than the seized vessel. This suggested that perhaps none of these vessels was in fact the ‘real’ NAHAM-4 – meaning there may be as many as five vessels bearing this name.

Investigation confirmed that the documentation provided for the port entry to Cape Town had been falsified and neither the Omani owners, Al-Naham Co LLC4, nor the ship’s agent, Trade Ocean, could prove that the vessel was the NAHAM-4. Links to the Oman based company Seas Tawariq Co. LLC were detected, they are the owner of the infamous IUU fishing vessel TAWARIQ-1, arrested and confiscated by Tanzania in 2009.

July 2013: South African Authorities seized both the vessel and the fish on board.

September 2013: Al-Naham and its representatives, Wu Hai Tao and Wu Hai Ping, were charged and convicted on seven counts relating to contraventions of South Africa’s Marine Living Resources Act and IOTC’s Conservation and Management Measures.

2013: The ship owners abandoned the vessel, leaving the agent with debts amounting to USD 100 000. The vessel and fish on-board were forfeited to South Africa, both were auctioned.

2015-2016: Renamed the NESSA 7, FISH-i Africa track the vessel from South Africa to South America, Namibia and finally to Mozambique where she is inspected by the authorities, arrested and confiscated.

How?

The evidence uncovered during FISH-i investigations demonstrates different methods or approaches that illegal operators use to either commit or cover-up their illegality and to avoid prosecution.

Vessel identity issues: With no mandatory identification system fisheries inspectors rely on vessel names, which can be easily painted over to fit with available licences or to hide a history of non-compliance, as was the case with the NAHAM-4 name.

Business practices: A complex network of company ownership raised challenges with the accurate identification of the beneficial owner. Threats were made to a journalist that was delving into the Omani registration and business aspects of Al-Naham Co LLC., raising suspicions that corrupt practices were taking place in Oman.

Document forgery: Four different vessels operated as the NAHAM-4 providing evidence that at least three of these were fraudulently using this name, documents were also identified as forgeries by South African authorities.

Flagging issues (suspected): The owners of NAHAM-4 do not appear to have any connection to Oman, the flag State so there is suspicion that flagging to Oman was intentional to benefit from Oman’s limited application of their responsibilities.

What did FISH-i Africa do?

- Used analytical tools and investigative techniques to gather and share intelligence.

- Analysed photographic evidence to reveal the previous name of the vessel.

- Communicated with the authorities in Belize.

- Cooperated with the Omani press to raise awareness with the authorities in Oman.

- Investigated ownership of the NAHAM-4 and links to the infamous TAWARIQ-1.

- Publicised the case using the media and the Stop Illegal Fishing website.

What worked?

- A port inspection identified the identity issues and triggered the investigation.

- Systematic cross checking of information highlighted anomalies.

- Accessible photographs of fishing vessels, drawn from a range of sources, provided crucial evidence of the number of vessels using a single identity.

- Investigative tools supported the investigation by mapping connectivity and nodes of activities.

What needs to change?

- A global, mandatory means of identifying commercial fishing vessels through the allocation of a unique vessel identifier such as an IMO number.

- Publically available photo databases of fishing vessels would help to prevent identity fraud.

- Flag States must inspect their fishing vessels, monitor their activities and act when non-compliance is detected.

- Tougher penalties that not only deter illegal activity, but once identified stop those involved from continuing to operate in the fisheries sector.

- INTERPOL engagement that encourages strengthened cooperation between national police and fisheries authorities to progress investigations.

FISH-i Investigations

In working together on over forty investigations, FISH-i Africa has shed light on the scale and complexity of illegal activities in the fisheries sector and highlighted the challenges that coastal State enforcement officers face to act against the perpetrators. These illegal acts produce increased profit for those behind them, but they undermine the sustainability of the fisheries sector and reduce the nutritional, social and economic benefits derived from the regions’ blue economy.

FISH-i investigations demonstrate a range of complexity in illegalities – ranging from illegal fishing to fisheries related illegality to fisheries associated crime to lawlessness.

In this case evidence of illegal fishing and fisheries related illegalities were found.