Moving Tuna: Transhipment in the Western Indian Ocean

The point when catch moves from the fishing vessel and enters the supply chain provides a critical point to monitor and check that it has been caught legally and in compliance with national and regional regulations. In our new report ‘Moving Tuna’ Stop Illegal Fishing looks at the role and scale of transhipment in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO) and identifies the risks, costs and benefits involved.

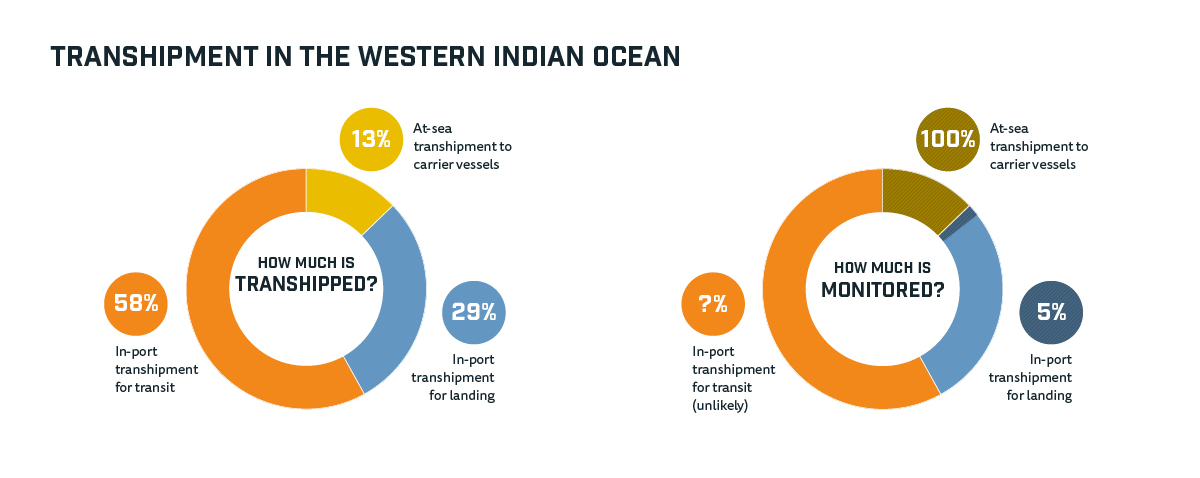

In the WIO transhipment takes place in three ways: at sea from a fishing vessel to a carrier, in port for landing, and in port for transit. Of these it is at-sea transhipment that receives most attention globally and is commonly seen as a facilitator of both illegal fishing and modern day slavery. Yet, in the WIO this makes up only 13% of tuna transhipped and under the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) regulations takes place with 100% observer coverage. This makes at-sea transhipment the best-monitored element of the tuna fishery in the WIO.

In contrast in-port transhipment for landing and in-port transhipment for transit make up nearly 90% of transhipped tuna and are far less likely to be monitored, if at all. This imbalance in scrutiny and oversight has implications for vulnerable fish stocks and highlights the need to urgently and systematically implement port State measures.

A further imbalance is seen in the burden for fisheries protection and monitoring. Today, while flag States pay for monitoring at-sea transhipments, port States pay for monitoring in-port transhipments. With limited capacity and resources and with the tuna often only transiting through port States a significant monitoring gap has developed. These issues need to be addressed to achieve sustainable development goal (SDG) 14.4 to end overfishing and IUU fishing.

Transhipment in the Western Indian Ocean: how much is transhipped? How much is monitored?

As blue economy agendas and SDG 14.7 focus to increase the economic benefits to developing countries from the sustainable use of marine resources, becomes more prominent, an understanding of how transhipment brings costs and rewards is required. ‘Moving Tuna’ demonstrates that today, European and Asian interests dominate the purse seine and longline tuna value chain and current opportunities for African coastal States to domesticate and benefit from the industry, to build local supply chains, add value and feed local demand are limited.

Moving Tuna provides three recommendations for transhipment management:

Regional transhipment monitoring – to monitor all at-sea and in-port transhipments from industrial fishing vessels within the same region or fisheries, using independent professionally trained and supervised observers, applying the user pay principle so that fishing vessel owners carry the cost.

Comprehensive validation of information – transhipment offers an operational bottleneck for compiling information about the fishing, vessels, catch and crew, but the real benefits come when this information is pooled with other MCS information and regionally validated, to provide a more accurate and complete picture.

National incentives attracting transhipment to local ports – including requirements or incentives in blue economy and fisheries development strategies to attract fishing and carrier vessels to tranship in ports near the fishing grounds to reduce pollution and emissions, build long-term business partnerships and to secure a supply of fish to drive African social and economic growth.

Credits

Moving Tuna is based on a study conducted by NFDS exploring the business ecosystem for tuna transhipment in the Western Indian Ocean. Support for this project was provided by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the Walmart Foundation.