Fish-i investigation: 16

Regional and international cooperation nets illegal fishing vessel

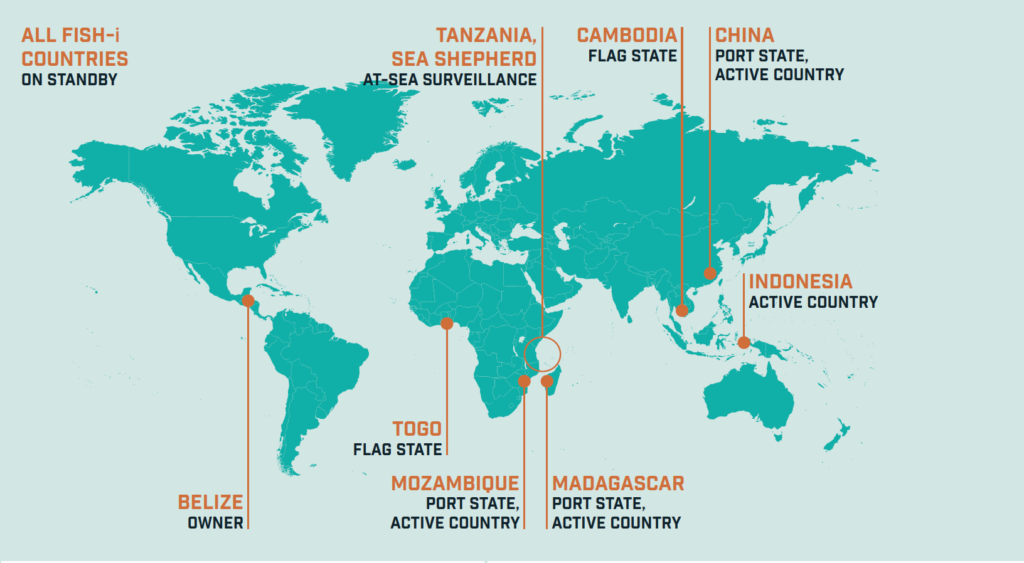

After initial arrest by Chinese authorities the STS-50, a vessel IUU listed by CCAMLR for its role as a carrier vessel for toothfish poachers, fled to the Western Indian Ocean. Using false information and fake documents the vessel sought bunkering and repairs from ports in the region, and was thought to be operating as a fishing vessel. With all FISH-i ports on high alert, the vessel headed for Asia. Using AIS tracking, FISH-i was able to follow the movements of the STS-50 leading to its ultimate arrest by the Indonesian Navy.

Key events

October 2016

The ANDREY DOLGOV, a Cambodian-flagged, Belize-owned refrigerated transport vessel, was IUU listed by CCAMLR for attempting to offload illegally caught toothfish in China. Mauritius denied a port entry request from the vessel and FISH-i members were alerted to the presence of the vessel, now renamed SEA BREEZ 1, in the Western Indian Ocean.

January 2017

The SEA BREEZ 1 was flagged to Togo through the country’s privatised open registry in Greece.

June 2017

Information on this high-risk vessel was shared with the West Africa Task Force and Togo confirmed it had been deflagged.

October 2017

Using the name AYDA the vessel was arrested in China. It fled port on the same day.

February 2018

Using the name STS-50, the vessel calls at port in Madagascar and was identified as ANDREY DOLGOV. The captain provided a false IMO number and forged documents. Madagascar alerted CCAMLR, port States and FISH-i who tracked the STS-50, transmitting over AIS using a generic MMSI, as it headed to Mozambique.

March 2018

The STS-50 failed to request permission to enter the Mozambique EEZ and a multi-agency team was deployed to inspect. On board, fishing gear was found, though the vessel was not licensed nor authorised to fish. Vessel documents and passports were seized and the STS-50

was taken to Maputo for investigation. She departed from Mozambique without permission and FISH-i members were alerted that the STS-50 would be looking to refuel and take on supplies.

Track analysis enabled FISH-i to monitor the STS-50 and keep the Regional Maritime Information Fusion Center (RMIFC) in Madagascar updated as she travelled through international and territorial waters.

Sea Shepherd vessel Ocean Warrior, on a joint operation with Tanzania and FISH-i pursued the STS-50 for several days, providing confirmation of her position.

April 2018

FISH-i provided positional data to the RMIFC in Singapore, which was relayed to countries in the region and contributed to the interception and arrest of the STS-50 as she entered the Indonesian EEZ. A multi-agency team investigated the STS-50 for fishing violations and for the trafficking of the 20 Indonesian crew members.

Togo initiated prosecution through their Ministry of Transport for the illegal use of the Togolese flag.

How?

The evidence uncovered during FISH-i investigations demonstrates different methods or approaches that illegal operators use to either commit or cover-up their illegality and to avoid prosecution.

Vessel identity

The STS-50 used name changes and misspelling of names to avoid arrest. By transmitting under a generic MMSI it tried to avoid tracking and arrest.

Flagging issues

Changes of flag State were made to hide the vessel’s IUU listing. Togo’s use of a privatised open registry to flag vessels provided limited information to the Togolese authorities.

Avoidance of penalties

Absconding from detention by Chinese and then Mozambican authorities and leaving without crew passports and vessel documents, avoiding port calls, hiding their AIS identity and changing flags all appear to be attempts to avoid sanctions.

Business practices

The owner and operator of the STS-50 are run through a Belize based shell company, making identification of beneficial owners, and enforcement of penalties challenging. It is reported that the Indonesia crew were deliberately misled into working on this vessel with their wages then being unpaid. Corruption may have enabled the escape of the STS-50 from detention in China and Mozambique.

Document forgery

The documents presented to the Togo registry were forged, making the flag fraudulently obtained.

What did FISH-i Africa do?

- Mauritius denied the vessel port access as it was IUU listed.

- Madagascar identified the vessel as an IUU listed vessel.

- AIS tracking of the vessel alerted Mozambique to inspect and bring the vessel into port for further investigation.

- Monitored the vessel’s activities over a three-week period.

- Shared positional information amongst the Task Force, Regional Maritime Information Fusion Centers in Madagascar and Singapore, and Indonesia.

- Liaised with the West Africa Task Force, particularly to verify Togo as flag State.

- Coordinated with Sea Shepherd vessel Ocean Warrior to pursue the vessel.

What worked?

- Routine port control verification in Madagascar identified the STS-50 as an IUU listed vessel.

- Port State measures were utilised to deny access to a known IUU listed vessel by Mauritius.

- AIS analysis was able to locate the vessel resulting in inspection by Mozambique, and tracking of the vessel until its detention by Indonesia.

- Due diligence, including document • verification, identified forged documents were used to obtain a Togo flag.

- Cooperation with Indonesia and the Maritime Fusion Centers led to the interception of the STS-50 when it fled the Western Indian Ocean.

What needs to change?

- Physical measures need to be in place to prevent vessels absconding when under investigation, or when detained in port.

- Photographs of fishing vessels need to be made accessible/publicly available.

- Mandatory unique vessel identification is needed, e.g. IMO numbers, to make it more difficult to hide the identity of vessels.

- Flag States need to conduct adequate due diligence when registering vessels.

- AIS needs to be linked to vessel identity, mandatory and tamper-proof.

FISH-i Investigations

In working together on over forty investigations, FISH-i Africa has shed light on the scale and complexity of illegal activities in the fisheries sector and highlighted the challenges that coastal State enforcement officers face to act against the perpetrators. These illegal acts produce increased profit for those behind them, but they undermine the sustainability of the fisheries sector and reduce the nutritional, social and economic benefits derived from the regions’ blue economy.

FISH-i investigations demonstrate a range of complexity in illegalities – ranging from illegal fishing to fisheries related illegality to fisheries associated crime to lawlessness.

In this case evidence of illegal fishing and fisheries related illegalities were found.