Issues

Global losses to illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing are estimated to be as high as 23.5 billion USD annually as well as significant loss of livelihood and damage to the natural ecosystem. Illegal operators are driven by money and key hotspots for their operations include the oceans and waters of Africa.

IUU fishing often goes hand in hand with other illegal or criminal activity. Stop Illegal Fishing has identified that fisheries related illegalities or crimes are those that facilitate IUU fishing and make it more profitable or easier (such as tax evasion, fraud, corruption or human rights abuse), while fisheries associated illegalities or crimes are those that take place in the fisheries sector but do not facilitate IUU fishing (such as drugs smuggling, human trafficking or the trade in illegal wildlife products).

Stopping illegal fishing therefore requires coordinated action at local, national, regional and international levels.

Vessel Identity

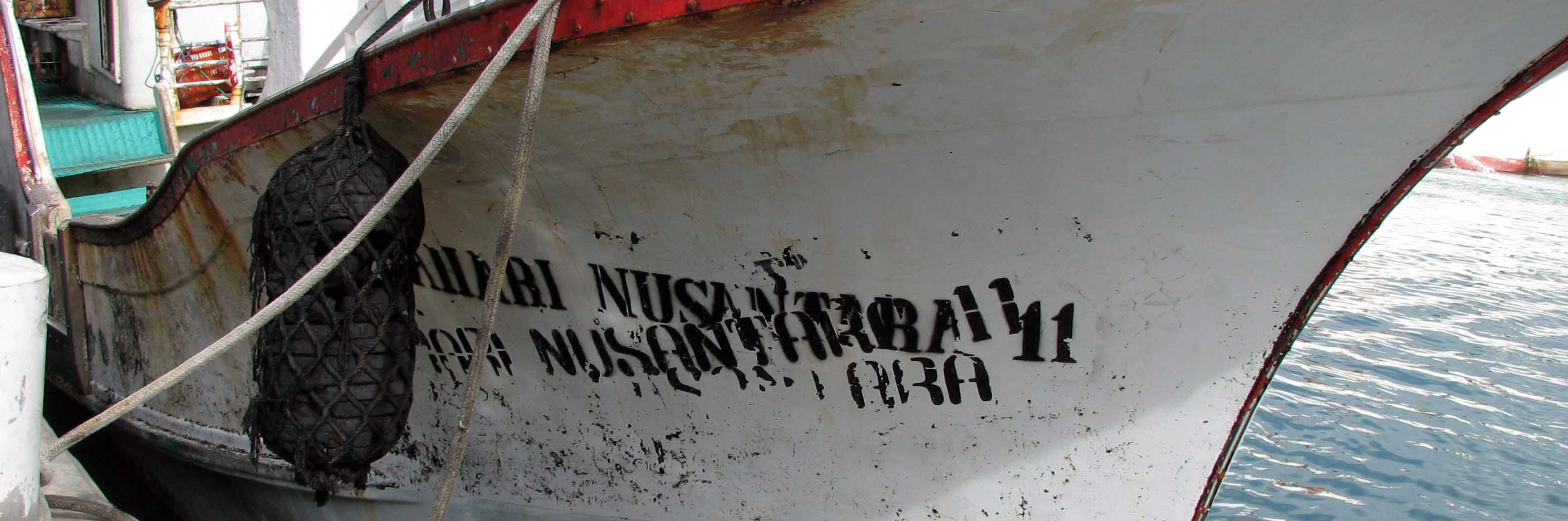

Illegal operators use vessel identity fraud to get away with illegal fishing. This can be one vessel illegally using several names or flags or several vessels using the same name. Mandatory IMO numbers are needed to help stop identity abuse.

It can be very difficult to identify a rogue fishing vessel with any degree of certainty. Most sea-going vessels are required to have a unique identifying ‘IMO number’ which is permanently marked on the ship’s hull or superstructure, rather like the engine number of a car. Fishing vessels, however, are exempt and there is currently no global record of fishing vessels, making it difficult to keep track of boats which change name, ownership or country of registration (‘flag’).

Some of the more irresponsible flag States, the so-called Flags of non-compliance do not check the history of a vessel applying to reflag, making it easy for a vessel to change identity. This means that it is difficult for coastal states and Regional Fisheries Management Organisations to find out if a vessel applying for a fishing licence has been involved in illegal fishing, and for port authorities to check the legitimacy of vessels wanting to offload fish.

Once suspected of illegal fishing, vessels might change name to be able to offload their catch or to continue fishing without being arrested. Alternatively, if a licence is granted to one vessel, for tuna long-lining for example, several vessels may take up that identity and use forged copies of the licence to fish themselves, circumventing catch restrictions. One notorious fishing vessel, Thunder, used 8 different names, had 9 owners and was registered with 8 different flag states during its 46-year history.

False AIS Transmissions

Since 2002 ships have been required to make ‘AIS transmissions’ which allows their position to be tracked as a way of avoiding collisions in busy sea lanes, but there is no way of validating AIS data. Ships can easily transmit false GPS co-ordinates, false identities or simply ‘go dark’ and not transmit. So, a vessel might use a fake identity while fishing illegally then switch to its real identity when heading for port to offload, concealing its illegal activity and the origin of the fish. According to a Windward report, Chinese fishing vessels account for 44% of all GPS manipulations, and “fish wherever they want”.

The Naham-4

In March 2013 a tuna long-liner, the ‘Naham-4’, was detained in Cape Town after inspectors became suspicious when they found a second faded name, ‘Der Horng 569’ painted on the hull. Stop Illegal Fishing, through FISH-i Africa were also investigating the Naham-4 as part of a routine check of vessels operating in the Western Indian Ocean and a comparison of photographs of vessels bearing that name showed that there were as many as five vessels going by the same name. The vessel was seized and eventually sold, only to be arrested once again in March 2016 (as the Nessa 7) for fishing illegally in Mozambican waters.

Read the full case study: The Mystery of the Naham-4

The Way Forward

- The FAO is working towards a global record of fishing vessels, it is important that regional bodies such as the FCWC WATF and the SADC MCSCC move towards regional registers or lists of fishing vessels to enable regional implementation and links to the global record.

- Since December 2013 fishing vessels have been able to obtain IMO numbers voluntarily; so far less than 15% of the estimated 185,600 fishing vessels over 100 GT or 24m have done so.

- IMO numbers are now mandatory for EU vessels over 100 GT or 24m length operating in EU waters and for EU vessels over 15m length operating elsewhere.

- Cooperation and sharing of information and intelligence between countries and RFMOs is essential to tackle this global problem.

Flags of non-compliance

Flag States who sell their flag to fishing vessels without checking the history of the vessel, that it is safe and seaworthy, that it is the vessel it claims to be and who do not take responsibility for the actions of the vessels are known as flags of non-compliance.

Flag States who sell their flag to fishing vessels without checking the history of the vessel, that it is safe and seaworthy, that it is the vessel it claims to be, and who do not take responsibility for the actions of the vessels are known as Flags of non-compliance.

Every state can register ships and in doing so grants its nationality to ships flying its flag; it then becomes responsible for ensuring that its flagged vessels act according to international law, wherever they are located. Ships are governed by the rules and regulations of the state whose flag they fly and cannot be flagged to more than one country. In theory there must be a ‘genuine link’ between the state and the ship, but this is not defined, and many countries operate ‘open registers’ which are available to any ship-owner regardless of nationality – which can be a useful source of revenue.

This is not a problem – if the flag state is able and willing to carry out its responsibilities, but flags of non-compliance do not.

There are many advantages of operating under a flag of non-compliance for illegal fishers:

- Registration is quick and easy and can be done over the internet for a few hundred dollars.

- No questions are asked about previous history of IUU fishing or the condition of the vessel.

- Owners avoid regulations enforced by their own countries.

- Gaps in international regulations means that it is not illegal to fish on the high seas even in a regional fisheries management organisation (RFMO) area, so a vessel can disregard management arrangements by flagging to a country that is not party to an agreement.

- RMFO inspectors cannot board a vessel without permission of the flag state, which is often withheld by flags of non-compliance.

- Labour legislation can be avoided.

- Taxes are low or non-existent.

- The identity of the owners is often hidden – some registers advertise their anonymity.

- Vessels can re-flag and change names several times in a season to confuse fisheries authorities and avoid prosecution for IUU fishing.

There is no easy solution, and even responsible states have room for improvement. While changing country of registration or ‘flag hopping’ is common practice for vessel owners involved in illegal fishing.

One such example is the fishing vessel Yongding, long suspected of illegally catching Patagonian toothfish, the vessel was finally detained in Cape Verde in 2016. It wasn’t easy to track the vessel down; like many other illegal fishing vessels, it had registered under nine countries or ‘flags’, including many notorious flags of non-compliance, and operated under at least 11 different names since 2001.

Human trafficking

Human trafficking occurs when workers are tricked into working on fishing vessels: their wages are unpaid, they live and work in unsafe and unsanitary conditions and they are far from land for months or years at a time with no opportunity for escape.

Tricked, trapped and trafficked, workers on fishing vessels often slip under the radar of the protection offered by labour and related laws. Human trafficking occurs when workers are tricked into working on fishing vessels: their wages are unpaid, they live and work in unsafe and unsanitary conditions and they are far from land for months or years at a time with no opportunity for escape. Harsh and violent treatment of crew has been reported as widespread.

“The six crew members of the fishing vessel Vicmar A …are on board the ship in subhuman conditions, without light, water or food on board; some of them are in poor health with no medical assistance. Safety on board the ship… is also compromised after a long period of neglect, and several months’ wages are owed. Employment contracts are also abusive and contrary to the law of (the flag state).”

This report, in Naucher Global in March 2015, four months after the vessel was abandoned in Equatorial Guinea, is just one glimpse into the terrifying reality of life onboard IUU fishing vessels.

Recruitment agencies, brokers and fishing operators deceive and abduct victims to get hold of crew – there’s a shortage of labour and few would willingly choose to work on vessels which are old, poorly maintained and have little or no safety equipment – typical features of IUU boats as they are likely to be forfeited if caught and so are treated as disposable. Usually sailing under a Flag of Convenience, international regulations concerning safety and working conditions can be ignored with impunity.

Deception is used to trick victims, who are often poorly educated or illiterate. Promises are made about work and pay, and contracts are issued, but these are often changed once the worker has flown to a foreign port. Fees mount up; recruitment fees, travel fees, even deductions for food, and these debts are transferred to the captain once the crew member is on board, turning him into a bonded labourer. Pay and passports are often withheld until a voyage has been completed, trapping crew members on board, even supposing they do reach port – but transhipment using reefer vessels allows ships to remain at sea for long periods of time, meaning there’s no escape for months or even years at a time.

Once at sea the realities of the working and living conditions become apparent − these are often poor and inhuman with limited food and only seawater for washing and laundry. With a minimum of 18-hour days and little pay, workers are often subject to violence and abuse. There are reports of physical injuries and deaths, suggestions that victims have been tossed overboard when sick, injured or dead and that crew that fall overboard are sometimes not rescued.

The identification of trafficked fishers is a challenge:

- IUU vessels may seldom visit port and prefer ‘Ports of Convenience’ with lax control measures.

- International security regulations require foreign crew to stay on board a vessel when in port.

- The welfare of fishers usually falls outside of the mandate of fisheries inspectors.

- Limited or no access of crew to authorities and a lack of trust in them.

- Lack of training and capacity of authorities and particularly the police.

- Belief that trafficking only relates to sexual exploitation.

- Language barriers.

- Trafficking victims avoid identification due to shame or fear of blacklisting.

When no longer useful vessels and/or crew may simply be abandoned, leaving crew stranded without the means to make their way home, reliant on charity, moneylenders or local people, and vulnerable to extortion by local officials. Once home, reintegration is difficult, involving health related, psychological and social challenges.

Human trafficking is a crime, but as fishermen pass through multiple jurisdictions, prosecuting this crime can be difficult and targeting senior crew for their role in trafficking does not get to the root of the problem – the criminal fishing operators hidden behind complex corporate structures designed to conceal their identity.

Transhipment

At sea transhipments are one of the major missing links to understand where illegally caught fish finds its way to the market. Unauthorised transhipment enables illegal operators to avoid port controls and to maximize profits.

Transhipment is often considered to be one of the major missing links in understanding where illegally caught fish finds its way to the market and thus a key cause of lack of transparency in global fisheries. Unauthorised transhipment enables illegal operators to avoid port controls and to maximize profits.

Like high seas fishing operations in all the worlds’ oceans, it is more efficient for vessels catching high-value fishlike tunas to stay out at sea for as long as possible. Travelling to and from port to offload their catch takes up valuable time (and fuel) that could be used for fishing. So, it’s common practice for refrigerated transport vessels, commonly referred to as ‘reefers’ or ‘carriers’ to do the fetching and carrying for them. It’s a highly organised system – reefers arrive at a pre-arranged time and place, bringing supplies of fuel, food, bait and even a change of crew, and take away the catch – frozen fish destined for foreign markets across the globe. This practice is known as at sea transhipment.

It’s highly efficient, but difficult to control. If a fishing vessel offloads or tranships in port, in principle, it is easier to inspect and monitor, although this may not always happen, to check that the catch was legally caught, but on the high seas this can be difficult to do. Illegal fishers take advantage of this and use transhipment to ‘launder’ illegally caught fish; by mixing illegal and legal fish the illegal fish takes on the documentation of the legal fish. Also, because reefers do not fish, they are often exempt from catch documentation and monitoring, creating a missing link in the chain of custody from vessel to plate.

In Ghana an artisanal form of transhipping, known as ‘Saiko fishing’ is conducted by local fishers who go out in canoes to meet foreign IUU vessels and transport boxes of frozen fish to processors who wait on shore. This practice, illegal under Ghanaian fisheries legislation, is driven in part by the depletion of fish stocks in the artisanal fishing zone resulting from this IUU fishing, and its consequences to the local economy, driving artisanal fishers to seek alternative forms of income generation like Saiko fishing – a vicious cycle.

Transhipment at sea can also facilitate labour and human rights violations as it enables fishing vessels to remain at sea for months or even years at a time, trapping crew members on board and leaving them vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. According to a UNODC report it is also used as a means of trafficking drugs in West Africa.

Transhipment at sea is one of the major missing links in understanding how illegally caught fish finds its way to the markets and thus how to fight this illegal trade. The FAO recommends:

- Coastal countries should consider requiring that all transhipments take place in port or, at a minimum, require that transhipment at sea is done in accordance with proper controls and at locations where inspectors can be present to check the details of the fish being transhipped.

- Flag States should consider prohibiting transshipment of fish at sea or at a minimum, require prior authorization for transshipment at sea and reporting of catch information.

- Regional fisheries management organisations (RFMOs) should adopt port inspection schemes and restrictions on transhipment at sea.

- Flag States should require their vessels to use a vessel monitoring system (VMS), a satellite-based tracking system that provides real-time information on vessel identity and activity.

Stop Illegal Fishing has been working to better understand the use of illegal transhipment, the implications for illegal fishing operations and how illegal fish is fed into the supply chain. Finding out who is involved and what networks are operating to allow them to happen under the radar of control and enforcement are critical in bringing this practice to an end.

Shark finning

Shark fins attract a premium price in the Asian market, so are cut off whilst the rest of the shark is thrown overboard often still alive. Unable to swim properly, they suffocate or die of blood loss from their huge wounds.

Shark fin soup – a traditional Chinese delicacy dating back over a thousand years, popular as a prestigious dish served to impress your guests, eaten at wedding celebrations and at New Year. Hong Kong restaurants may charge up to a staggering 250 USD a bowl for the best shark fin soup, said to be made out of the fins of hammerhead sharks, but you can also buy it cheaply from street vendors for less than 1 USD; it’s widely consumed throughout Asia, and appears on menus worldwide. Hong Kong is the shark fin trading hub, accounting for more than half of the world trade. With the increase in prosperity in the Far East in recent years, there is an increasing demand for shark fins, but what is the true cost of shark fin soup?

What is shark finning?

As the trade in shark (and ray) fins can be so lucrative, it is very attractive to fishermen and middlemen – and organised crime syndicates. In contrast to fins, there is less demand for shark meat (fins are worth 20 to 250 times the value of meat by weight) so instead of landing whole sharks, which take up space on board, the fins are cut off the sharks, often while they are still alive and the rest of the shark is thrown overboard. Unable to swim properly, they suffocate or die of blood loss from their huge wounds – the marine equivalent of elephant and rhino poaching.

Much of this ‘shark finning’ occurs far offshore, away from the reaches of enforcement vessels. For example, a lack of patrol vessels means that the offshore fisheries in Mozambique are largely unregulated and longliners with licenses for tuna may instead target shark, even switching gear and using gill nets to fish for shark. A 2005 report estimated that hundreds of Taiwanese fishing vessels were operating shark-fin fisheries offshore of Africa and the Middle East in the Western Indian Ocean. Fins were transhipped to freezer carriers and transported to Asian ports. But shark finning is not just happening offshore. In southern Mozambique Chinese nationals buy fins from artisanal fishers and smuggle them out of the country via Maputo or the Bazaruto Archipelago. It is said to be a huge and organised industry.

Shark finning is not just occurring in unregulated fisheries. The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), Southeast Atlantic Fisheries Organisation (SEAFO) and Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) all require full utilisation of entire shark catches, but do allow fins to be removed at sea provided all parts of the shark are utilized and the weight of fins landed does not exceed 5% of the weight of the carcasses. The reason given for needing to remove the fins is that it makes the sharks easier to store, but Costa Rica has shown that whole sharks can be stored efficiently by partially cutting the fins and flattening them against the body before freezing. The 5% ratio of fin to body weight is considered to be high, so it’s not too difficult to sidestep the law.

Effect on shark populations

Cruelty and ethics are only part of the story. Sharks are vulnerable to fishing for several reasons: they grow slowly, are slow to mature, have long gestation periods and produce relatively few pups. It’s thought that around 100 million sharks are killed each year and according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species a quarter of the world’s sharks and rays are threatened with extinction. They are also vulnerable to pollution; toxic chemicals become increasingly concentrated towards the top of the food chain, and as sharks are apex predators their bodies can contain very high levels of toxins like mercury, affecting reproduction. The decimation of top predators like sharks can have devastating effects on entire ecosystems.

What can be done?

Ban the removal of fins at sea. In Africa shark finning is banned in Gambia, Guinea, Seychelles (without authorisation), Sierra Leone and South Africa. All shark fishing is banned in Congo-Brazzaville.

Protective legislation is needed for endangered species of sharks and rays.

Ban transshipment at sea- transshipment is used to avoid proper catch reporting and to launder IUU caught fish.

Increase observer coverage on ships.

Improve the implementation of port state measures to track down IUU fishing.

Given the difficulties of enforcing regulations, perhaps what is needed most is education. In an attempt to reduce the prestige of shark fin soup the Chinese government prohibited it at official banquets in 2012 and celebrities are starting to speak out against the practice. But there’s a long way to go – a recent survey found that shark fin soup still served at 98 per cent of Hong Kong restaurants.

Market Access

Trade-based measures play a huge role in stopping illegal fishing and increasing compliance. For example, the EU, as a major market for fishery products, are driving change through the EU-IUU regulations introduced in 2010.

It has been estimated that global losses due to illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing could amount to 10-23 USD billion annually, with almost 1 USD billion for sub-Saharan Africa – about 19 percent of the current landed value, with valuable high seas species being targeted in particular. The high seas are difficult and expensive to patrol, so land-based measures have a huge role to play in the battle against IUU fishing. The Port State Measures Agreement is one of the options in the toolbox – trade-based measures, in the form of restrictions placed on access to markets of IUU fish is another.

Two approaches can be taken:

- Ban the import of all fish and fish products from states that have a poor record of compliance to fishery regulations.

- Ban individual shipments that lack documentation to prove their legal provenance.

Catch documentation schemes (CDS) which enable fish to be traced back to the vessel that caught it are enforced by some regional fisheries management organisations (RMFOs), but not enough; of the approximately 17 RFMOs in place around the world, less than a third have a CDS in place. Schemes vary, but in general documents are required to accompany fish from the point of first capture through to its final destination. Such traceability — tracking seafood from boat to plate, makes it much more difficult to market illegal fish as there are many opportunities to detect it, when it is offloaded, imported, traded and/or re-exported through international trade routes.

In addition to RFMOs, the EU, Chile and the USA operate trade measures at the national level. The EU measures go one step further than those of RFMOs in that they apply to all wild-caught fish, whereas those of RFMOs apply just to their species of interest, for example tunas in the case of ICCAT and the IOTC. The EU measures also apply to fish originating from within exclusive economic zones as well as from the high seas. As the EU is the world’s largest importer of fish this could make a real impact, but there are several concerns:

- Developing countries may lack the resources and infrastructure needed to meet the EU requirements, although the EU may assist with capacity building.

- The cost of compliance for small-scale fisheries, in which each vessel may catch only a small amount of fish, is high as a catch certificate is required for each vessel.

- There is a risk of regulations being discriminatory, against World Trade Organisation rules.

- Delays caused by reporting requirements may be problematic for shipments of fresh fish.

- Instead of reducing IUU fishing it may simply shift IUU fish to non-EU markets.

However, trade measures have been successful in changing the behaviour of some countries; for example, Ghana implemented many changes including the strengthening of its legal framework and adoption of a National Plan of Action to Combat IUU fishing in order to avoid being ‘red-carded’ by the EU for failing to discharge its duties as a flag, port, coastal and market state.

Effectiveness of trade measures could be further increased by more regional cooperation between neighbouring states and RFMOs; sharing ‘black-lists’ of IUU vessels, harmonisation of catch documentation schemes and traceability requirements (the FAO has developed guidelines for this), and by placing embargos on states who have failed to take appropriate measures to ensure compliance by their vessels.

Blast fishing

Highly destructive and illegal, blast fishing destroys the marine environment, killing marine creatures indiscriminately, reducing future catches, affecting food security and the livelihoods of fishing communities.

Blast fishing is highly destructive and illegal. Dynamite or other types of explosives are used to send shockwaves through the water, stunning or killing fish which are then collected and sold. The blasts destroy the habitat, killing marine creatures indiscriminately, reducing future catches, affecting food security and the livelihoods of fishing communities.

Blast fishing usually occurs over coral reefs, shattering the coral and destroying these biodiversity hotspots for decades to come – it is thought that it may take more than a century before reefs return to normal. It’s also dangerous; devices sometimes explode prematurely, causing serious injuries and deaths.

Blast fishing occurs in over 40 countries worldwide. In Africa it has been particularly problematic in Tanzania, destroying Tanzania’s coral reefs and all the benefits they provide, and threatening the country’s international tourism industry as destroyed reefs and the danger of explosions drive tourists away.

However, the problem is far more complex than it appears on the surface. A Multi-Agency Task Team (MATT), formed in 2015 to tackle blast fishing and other environmental crimes uncovered a complex criminal network of organised crime syndicates involved, not just in blast fishing, but in illegal drug trafficking, prostitution and human trafficking, gun running, and wildlife and timber smuggling, often linked to businesses and high-profile individuals.

The MATT has addressed many of the factors that contributed to the prevalence of blast fishing in Tanzania:

- Low cost and easy accessibility of explosives from the mining and construction industries.

- Relatively easy methods of making home-made explosives from common ingredients.

- Income potential with each blast catching up to 400 kg of fish, worth up to 2,000 USD.

- Poverty and unemployment, and a lack of alternative income opportunities.

- Outdated and inadequate legal framework with ineffective penalties.

- Low rate of enforcement and prosecutions aggravated by corruption, bribery and intimidation of both officials and fishers.

Securing Convictions

Identifying illegal operators is difficult, but bringing them to justice, securing convictions and achieving sanctions that match the severity of the violations and that act as a deterrent is challenging.

There are huge profits to be made from illegal fishing. The vastness of the high seas and insufficient monitoring and enforcement facilities means that the chances of being caught are relatively low. But suppose, against the odds, a vessel fishing illegally is apprehended and brought into port, investigated, prosecuted and successfully convicted, all too often the resulting penalties are so low that to many illegal operators they are viewed as merely part of the operating costs. An example from an Oceana report says it all: “Penalties paid within the European community averaged between 1.0 and 2.5% of the value of IUU landings, effectively a cost of doing business rather than a deterrent.”

Illegal fishing continues largely unpunished for many reasons:

- Domestic fisheries legislation can be too complex and is often outdated. Countries may sign international treaties but then fail to pass adequate laws to implement them.

- Most fisheries offences are not treated as crimes; laws are usually designed to regulate the fishing industry rather than to deal with organised crime within it.

- Low penalties are not just a poor deterrent but indicate that fisheries crimes are considered low priority and consequently they receive less investigative effort by law enforcement agencies.

- Intelligence gathering is often hampered by a lack of transparency with respect to vessel ownership resulting from frequent vessel name changes, reflagging and complex corporate structures designed to hide the identity of the true beneficial owner.

- Communication between different agencies, such as fisheries inspectors, customs and police, even within the same port, is often inadequate or is hampered by confidentiality considerations.

- There is often poor awareness of fisheries laws among prosecutors and magistrates, and they are often not well informed about the magnitude and impact of fisheries crime.

- The global nature of IUU fishing means that it is very difficult for any one country or Regional Fisheries Management Organisation to achieve a successful conviction.

There is an obvious need to improve legislation; international conventions and agreements should be ratified and reflected in national legislation. The severity of penalties should be increased and should include prison terms. In response to the growing awareness of the complexity of fishing-related crimes there are an increasing number of initiatives being taken which show what can be done, for example:

Interagency cooperation: MATT (a multi-agency task team), was set up in 2015 in Tanzania to fight organised crime centred around blast fishing. It includes four ministries, the Intelligence Security Serve and the police and now tackles all environmental crimes in the country.

The establishment of specialist environmental courts and training of prosecutors and magistrates in South Africa, primarily to prosecute abalone poachers, resulted in conviction rates increasing from around 10% to 90% in two years.

International co-operation: in 2013 INTERPOL set up a special unit to fight IUU fishing which has achieved several successes, including that of the Thunder, successfully prosecuted by São Tomé and Príncipe for illegal catches of toothfish. A task force of 10 countries as well as INTERPOL were involved.

As these examples show, cooperation is the key to success – both within countries in the form of multi-agency collaboration and on an international level.

Observers

Fisheries observers are the “eyes and ears” of the sea, often working far from land for weeks or even months at a time in difficult and dangerous conditions, collecting the scientific information vital for management of fish stocks.

Fisheries observers are the “eyes and ears” of the sea, often working far from land for weeks or even months at a time in difficult and dangerous conditions, collecting the scientific information vital for management of fish stocks the world over – or rather, for those countries that have the means to develop and implement a fisheries observer program.

In order to manage fisheries in a sustainable way, managers need information – lots of it – on how much of each species was caught, the size and age of the fish, where it was caught, how much fishing effort it took to catch the fish, and also what was thrown away or caught unintentionally – the discards and bycatch levels which also impact on the functioning of the marine environment. Much fishing takes place far from land and the catch may be processed on board, frozen, packed and shipped off to distant markets. This is where fisheries observers come in.

Observer programmes in Africa have had mixed success with many floundering due to a lack of political commitment. However, there are exceptions. Namibia’s observer programme began in 2002 and received government commitment and long-term advice and financial aid from Norway to help train the hundreds of observers necessary to monitor Namibia’s fishing fleet. Today Namibia runs a globally respected observer programme with observers on upwards of 70% of vessels.

In a recent development 22 member states of ATLAFCO, African countries bordering the Atlantic Ocean, are working on a regional observer program to monitor the activities of foreign vessels in the EEZs of member countries. Regional cooperation is essential; with foreign tuna vessels often crossing several exclusive economic zones as they follow the stocks during a fishing trip, it is not practical to change observers each time a vessel crosses a national border.

Observers are not law enforcement officers, although they are increasingly being required to ensure that rules and regulations are correctly implemented and to report any violations. This function makes them vulnerable to bribery, threats of violence and actual physical abuse. How frequently this occurs is difficult to assess. An observer says that “every observer who has been doing it for very long has a story of being threatened or harassed at some point” although often this goes unreported due to fears for their job or of risking their safety on future trips. Reported transgressions are not always treated seriously; a Korean captain fishing in South African waters was caught trying to bribe and then threaten an observer after he had been taped fishing illegally, including carrying out shark finning, but the court released the captain with a light fine.

But there are reports of harassment and even deaths – observers have been lost at sea without trace, and there are strong suspicions that not all disappearances are accidents. The disappearance of Keith Davis, a “transhipment observer”, from a carrier vessel in broad daylight in calm seas off the coast of Peru in September 2015 was widely reported in the media but investigations by the FBI and others could find no evidence to suggest what happened to him. There are other reports, including one of two observers who vanished off Angola while monitoring foreign boats. To reduce the risks observers need:

- Training in basic survival and safety measures for the prevention of accidents.

- Training in how to identify, deal with, and document any instances of interference (including bribery), intimidation or obstruction by the vessel crew.

- Deployment of two observers per vessel for support especially on long trips.

- Back-up support from fisheries authorities is essential.